Activities: Other Animals Are Just Like Us (Grades 6-12)

We humans expend a lot of energy trying to differentiate ourselves from other animals in order to justify our treatment of them. We draw arbitrary lines between “us” and “them” and emphasize our differences. But the more we learn about and try to understand other species, the more we realize that humans aren’t that special. Other animals also learn languages, form complex social bonds with family and friends, sacrifice their own pleasure for the good of others, use tools, have dreams, play games, and entertain themselves. We all have our own memories and preferences, our lives are full of intimacy and drama, and we mourn when our loved ones die. Other animals are individuals, just as we are—and they’re much more complex than many humans care to acknowledge. Animals are just like us, because—spoiler alert—we are animals, too.

Just like humans, other animals are people. They have unique needs, wants, and personalities. Many have complex social systems, and they communicate in languages that we’re just beginning to understand. (Think of all that we don’t yet have a clue about!) And some species have capabilities that far exceed those of humans—in navigation, in the use of their senses, their physical endurance, their ways of communicating, and their ability to detect natural phenomena, for instance.

The following lesson plan is designed to help students see the many similarities between humans and other animals—as well as some of the astounding ways their abilities surpass our own. These lessons are designed to activate critical thinking and empathy in your students by helping them connect the dots and see that if animals are just as sentient, capable, and aware as we are, we have an obligation to protect them and give equal consideration to their needs.

Use the following activities to introduce these topics to your students, and incorporate the ongoing activities—which will help students learn about and relate to animals as fellow individuals—into your classroom.

Introducing Writing Prompts

Begin this lesson plan by introducing a new weekly practice: empathy-building writing prompts. TeachKind’s 39 writing prompts are quick and simple, and they can be used as weekly warm-ups that can help your students develop empathy and appreciation for all animals. Each of these prompts will not only teach students something new about animals (or help them consider something they already knew in a new light) but also encourage them to relate to animals on a personal level—a habit that can help build lasting empathy.

39 Images and Daily Writing Prompts That Will Help Your Students Develop Empathy for Animals

Explain to students that the purpose of the new exercise is to give them an opportunity to explore their own thoughts and feelings in a safe way while building empathy. Begin the activity by assigning up to three of the writing prompts, either as a classroom warm-up or a homework assignment.

All Animals Are Unique

The article “Are We Really That Special?” by Lisa Towell, which originally appeared on PETA Prime, explores some of the special qualities possessed by other animals that we often attribute to humans alone. Students will read this article in the next section of the lesson.

In the article, Towell refers to several animals and anecdotes:

- Koko, a gorilla who could understand spoken English and communicate using American Sign Language

- Alex, an African gray parrot who could count objects and use more than 100 words

- Elephants who have passed the so-called “mirror test,” which demonstrates self-awareness

- Scarlett, a cat who risked her life to rescue her kittens from a burning building

- Lulu, a pig who played dead in order to get help for her guardian, who was having a heart attack

Before reading the article, assign each student one of the five topics above and ask them to spend some time researching the topic online. Then ask them to write a page about it answering the following questions:

- Which animals or animals did you research? What makes them notable?

- What did you learn about this species through your research?

- What did your research suggest about animal sentience and consciousness in general?

You could either assign the research as homework or devote part of a class period to it. Once the assignments are complete, have students break into groups based on their research topics. Have them share their responses to the writing prompts with each other, then have each group choose one or more volunteers to explain their topic to the rest of class so that all students will have background information on each of the references made by Towell in her article prior to reading it.

Are We Really That Special?

After the background information has been presented, print and distribute copies of the article “Are We Really That Special?” to your students and have them read it.

Then give them each a copy of the “Author’s Purpose” worksheet. As background, tell students that every author has a purpose or reason for writing in a particular way. Explain that authors could write to inform, entertain, persuade, express feelings, or do even more—and they can have more than one purpose in writing a single text. Use examples of texts that you’ve read as a class to illustrate these various purposes.

After this explanation, use the “Author’s Purpose” worksheet to chart their categorization of the authors’ purposes in writing the “Are We Really That Special?” article. Discuss their responses as a class.

Animals Are Not Inanimate Objects

Ask for a student volunteer to define “noun”—they’ll likely say, “a person, place, or thing.” Write these three categories on the board. Ask students to volunteer to share qualities that separate the “person” category from the “thing” category, and write some of those qualities on the board. Some responses might be “Things are objects,” “People own things,” “People have brains,” or “People have feelings.”

Now ask students which category they think animals should be placed in and why. If anyone responds that animals are things, ask them to explain their reasoning. Note that many English speakers refer to animals using the pronoun “it” rather than “he” or “she”—and that when we refer to animals in this way, we’re implying that they’re things.

Nouns: Animals Don’t Belong in the ‘Thing’ Category

But if we classify animals as things, we’re perpetuating the idea that they’re inanimate objects, no different from the notebooks and pencils on your students’ desks. Of course, notebooks and pencils don’t suffer or die if they’re neglected, forgotten, or mistreated. They don’t feel pain, need food and water, think, form relationships, or feel emotions as animals do. Look at the qualities written on the board—can’t those in the “people” category apply to animals, too?

Next, print and then hand out copies of the “Animals Are Not Inanimate Objects” reading sheet by Ingrid Newkirk and have students read both pages in full.

After students read the text, have them respond to the following comprehension questions citing details from the text whenever possible to support their opinions:

- How does the author define “animal rights”? What do you think the term means?

- List at least five qualities that differentiate animals from inanimate objects. Cite examples from the text and come up with some ideas of your own, too.

- What are some examples of ways that human prejudice toward animals could be compared to prejudice against other groups of humans?

- Name three animal capabilities that humans don’t have, using examples from the text. Can you think of any other examples? If so, explain.

- Some people dismiss animal intelligence by chalking it up to “pure instinct.” In your opinion, is instinct less respectable than intelligence? Why or why not?

- The author cites falling in love as an example of instinct-based behavior in humans. What other human activities do you think are guided by instinct rather than logic?

- In the article, the author says that future generations are facing the following questions: “Who are animals?” “What are we doing to them?” and “Should we change our behavior, no matter how much we like our old ways?” Write your answers to these questions in paragraph form, using your own opinions or details from the text to support them.

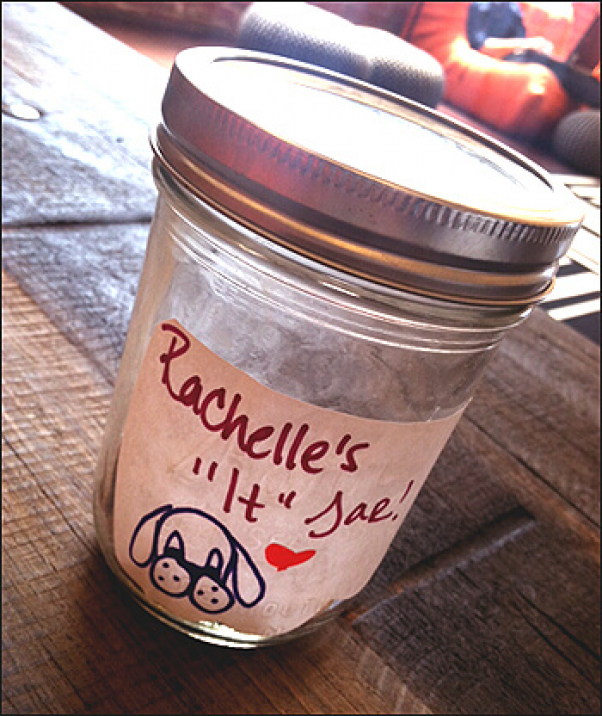

Changing Our Language to Help Animals

Our language has the power to shape reality, and our standards regarding the acceptable treatment of others are often conveyed through our words. If we categorize animals as things, as discussed in previous activities, we’re implying that they’re nothing more than inanimate objects—and that opens the door to harsh or negligent treatment despite their capacity for suffering. Explain to students that by simply changing our speaking habits and referring to animals as “he” or “she” instead of “it,” we’re making a statement to others about animal sentience and personhood—encouraging them to think differently about animals and how they’re treated by humans. Our words have the power to influence people to make positive changes in their own language and their behavior.

You can help solidify this concept by creating an “It” Jar in your classroom. Just decorate a jar and explain that every time anyone calls an animal “it,” you’ll keep track by placing a marble in it. (You can read the full “It” Jar instructions and supplementary activity ideas here.) Assign an “it” monitor (or have the class do the job together), and turn the ongoing lesson into a lighthearted game or contest to improve students’ language skills. Remind them that the point of this lesson is to help everyone improve and that no one will be made fun of or shamed for accidentally calling an animal “it”—this is a widespread habit, after all, which is why the activity is important.

Here are some ways to make the ongoing activity more exciting:

- Reward students who find examples of an animal referred to as “it” when they’re reading or watching a video.

- To motivate students to pay attention to their language involving animals, tell them that if the marbles in the jar reach a certain number, they’ll all be given an extra homework assignment—but make it easy and animal-friendly.

- Or alternatively, if the quantity of marbles stays beneath a predetermined level, reward the class with a homework-free weekend or some vegan snacks.

- Make it a competition, and have different class periods vie for the lowest number of marbles! Use a different jar for each class period, and reward the class with the lowest number of marbles at the end of the month.

- Use coins instead of marbles and at the end of the year, donate the money from the jar to your local open-admission animal shelter or to another animal-friendly cause voted on by the students.