Photo Gallery: Animals Used for Food

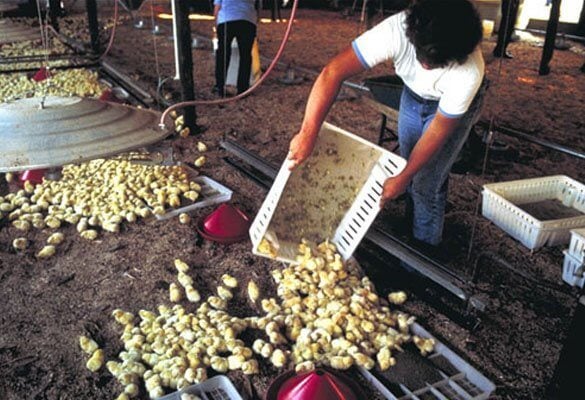

Chicks – Chicks raised for their flesh (“broiler chickens”) are dumped out of transport crates and onto the floors of massive sheds—the 9 billion chickens raised for their flesh every year in the United States won’t leave these filthy enclosures until the day they are sent to slaughter.

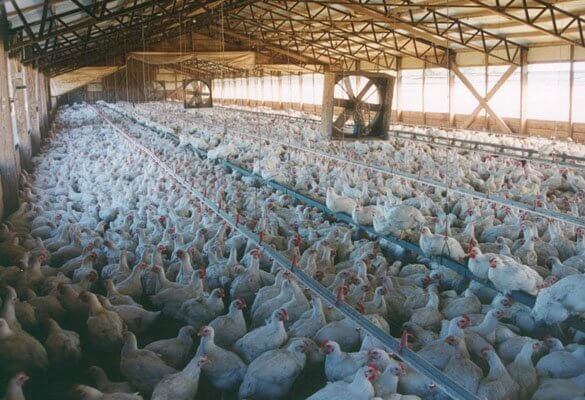

Broiler Sheds – With tens of thousands of chicks packed into each building, the sheds become increasingly crowded as the animals grow larger. Chickens often have to walk on top of one another—and over the bodies of others who have died—to get to food and water. Chickens function well in groups of up to about 90, which is a number low enough to allow each bird to find his or her spot in the pecking order. In crowded groups of tens of thousands, however, no such social order is possible, and in their frustration, chickens peck at one another, causing injury and death.

Debeaking – In order to keep the hens from pecking one another to death out of frustration in the crowded cages, each chick has a large portion of her sensitive beak sliced off with a burning-hot blade. She is not given any pain relief, and many birds are not able to eat because of the pain and die from dehydration and a weakened immune system. Even in the least-crowded cages in the industry (five hens per cage), each hen will spend her life with four other birds in a crowded space about the size of a file drawer, unable to spread even one wing.

In 2004 and 2005, PETA conducted an undercover investigation at a Tyson slaughterhouse in Heflin, Alabama, exposing obscene cruelty to chickens raised and killed for food. In 2020, two Tyson kill-floor workers came forward to share their stories, which confirmed that for chickens and workers, the company’s slaughterhouses are still hell on Earth.

Blood – At the slaughterhouse, chickens are hung upside-down in shackles on conveyor belts and have their throats slit, and their bodies are drained of blood. A river of blood and feathers flows beneath the conveyor belt.

Branding – To mark cows for identification, ranchers restrain them and inflict third-degree burns as the cows bellow in pain and struggle to escape. The cows are given no painkillers, and many are branded multiple times during their lives.

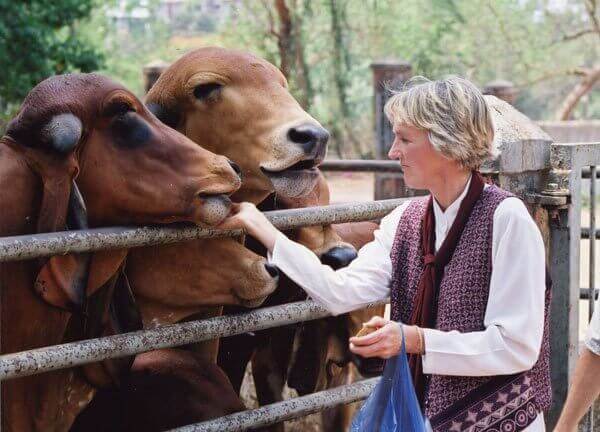

Milking – Cows produce milk for the same reason humans do—to nourish their babies. To keep producing milk, cows are forcibly impregnated through artificial insemination every year. The cow’s babies are generally taken away within a day of being born—male calves are destined for veal crates, while females are sentenced to the same fate as their mothers. Mother cows on dairy farms can often be seen searching and calling for their babies long after they have been taken away. The mother cow will be hooked up several times a day to machines that take the milk intended for her calf. Through genetic manipulation, powerful hormones, and intensive milking, she will produce about three times as much milk as she would naturally.

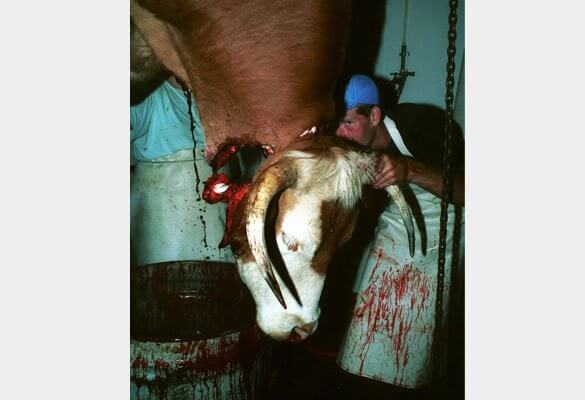

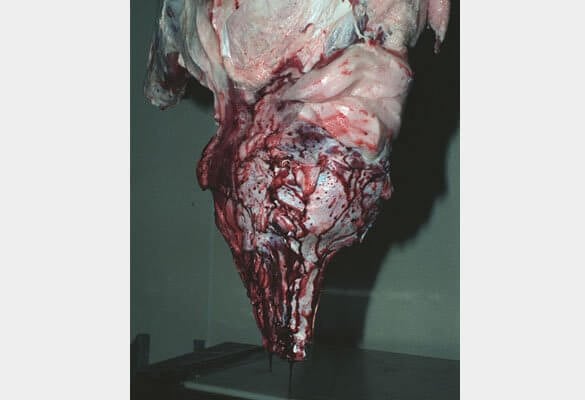

Slaughter – A worker saws a cow’s head off. Scientists know that the brain and spinal material of cows can cause the human variant of mad cow disease if consumed by humans, but the fast and shoddy butchering of the animals often causes brain and spinal material to spatter onto meat that is sold to the public. A study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2002 found that 35 percent of cow flesh contained “unacceptable nervous [system] tissues” that could cause the human variant of mad cow disease.

Slaughter – A skinned carcass is sawed in half. The worker is given little protective gear and risks serious injury on the job every day—one out of three slaughterhouse workers is injured on the job each year.

Slaughter – The sawed-off legs of cows are collected in barrels—they will later be rendered into fertilizer, dog and cat food, or feed for pigs and chickens in factory farms. The practice of feeding dead cows to other animals could be contributing to the spread of mad cow disease in the U.S.

Chicks – On turkey factory farms, baby chicks spend their first few weeks of life in giant, crowded incubators. When they are old enough to move to the warehouse with thousands of other turkeys, the farmers cut off the sensitive tips of their beaks, their toes, and the red flaps of skin under the males’ necks, all without pain-killers. Millions of turkeys die during their first few weeks of life from disease, infection, or stress.

Sick and Injured Turkeys – Many turkeys develop large, festering wounds as a result of the high levels of caustic chemicals like ammonia and hydrogen sulfide in the air. These chemicals emanate from the enormous amounts of feces in the sheds. Many factory farmed turkeys die from these wounds and other infections, and their bodies are sometimes left in the sheds with the survivors for days or weeks before they’re finally thrown in the trash.

Factory Farms – After they are debeaked, turkeys are crammed into enormous sheds: The air is laden with ammonia and is filled with particulate dust from feces and feathers that grates their lungs with every breath. Turkeys are bred and drugged to grow so quickly they often become crippled under their own weight. In fact, modern turkeys are so top-heavy that they can no longer mate naturally; all turkeys used for their flesh are the products of forced artificial insemination.

Transport – After about six months, the animals are grabbed by their delicate legs and slammed into crates on transport trucks, where they will travel for many miles through all weather extremes without food or water to the slaughterhouse. Many turkeys die before they reach their final destination. There are no laws regulating the transport of farmed animals on trucks. People who live near factory farms or slaughterhouses often reports seeing dead or dying animals who have fallen off trucks on the side of the road.

Slaughter – This turkey appears to be fully conscious and bleeding from her neck. At the slaughterhouse, turkeys’ sensitive legs are snapped into shackles and they are hung upside down. They are often still completely conscious and struggling to escape when their throats are cut open. Some turkeys miss the neck-cutter, and these terrified birds are still alive when they are dunked into the scalding water of the defeathering tanks.

Injured Sow – Many pigs develop open wounds because the ammonia from their waste burns their skin and the concrete floor rubs their skin raw.

Killing Sick and Injured Pigs – To cut costs, factory farm operators often don’t give individual veterinary attention to ill or injured animals. Instead, workers kill sick pigs who won’t be able to make it to the slaughterhouse or simply leave them alone to die. In one investigation, workers were videotaped killing sick pigs by repeatedly slamming them against the concrete floor.

Dead Pigs – Dead piles are a constant presence in factory farms. While pigs are fed massive amounts of antibiotics to keep them alive in conditions that would otherwise kill them, hundreds of thousands succumb to the stress of violent mutilations and intensive confinement. Dead pigs are sent to rendering plants, where they are made into dog and cat food or into feed that will be given to pigs, chickens, and other farmed animals.

Slaughter – A skinned pig is hung upside-down to drain the blood from her body.

Slaughter – A worker uses a chainsaw to cut a pig corpse in half.