See PETA’s president in person! After this event, you’ll have a new spring in your step, knowing you’re an integral part of the “all” in “all together now.” See a list of all upcoming tour stops and get your tickets here.

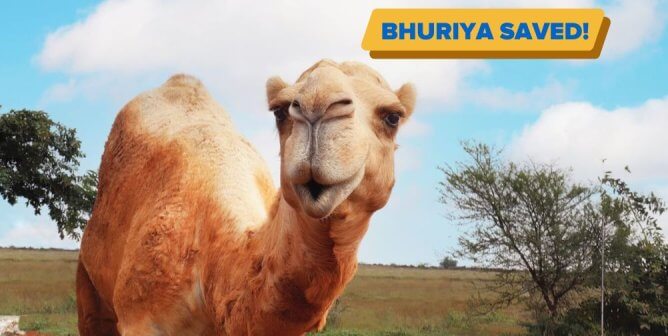

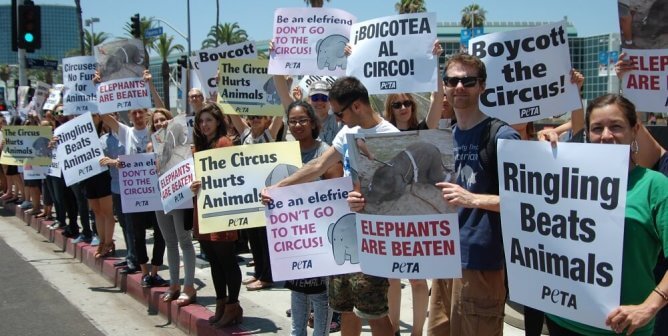

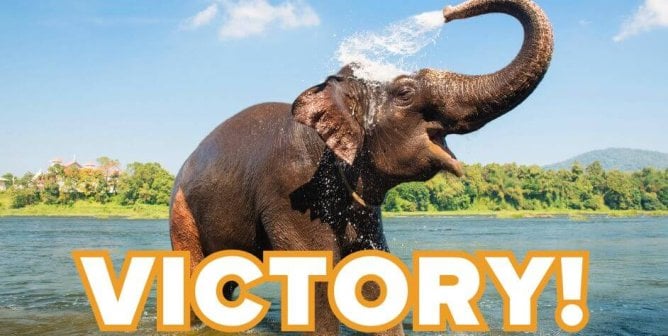

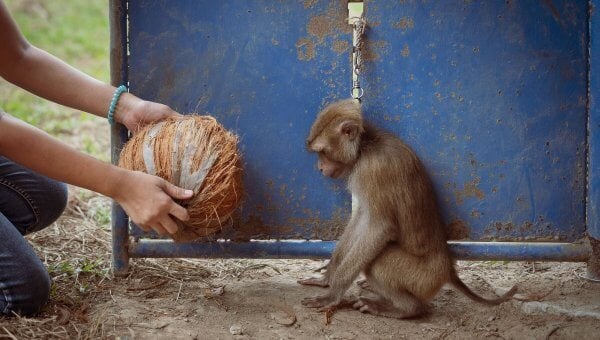

PETA IN ACTION

Urgent Alerts

Change the World for Animals—Take Action Now

WHAT PETA STANDS FOR

People

I am you, only different

Ethical

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Treatment

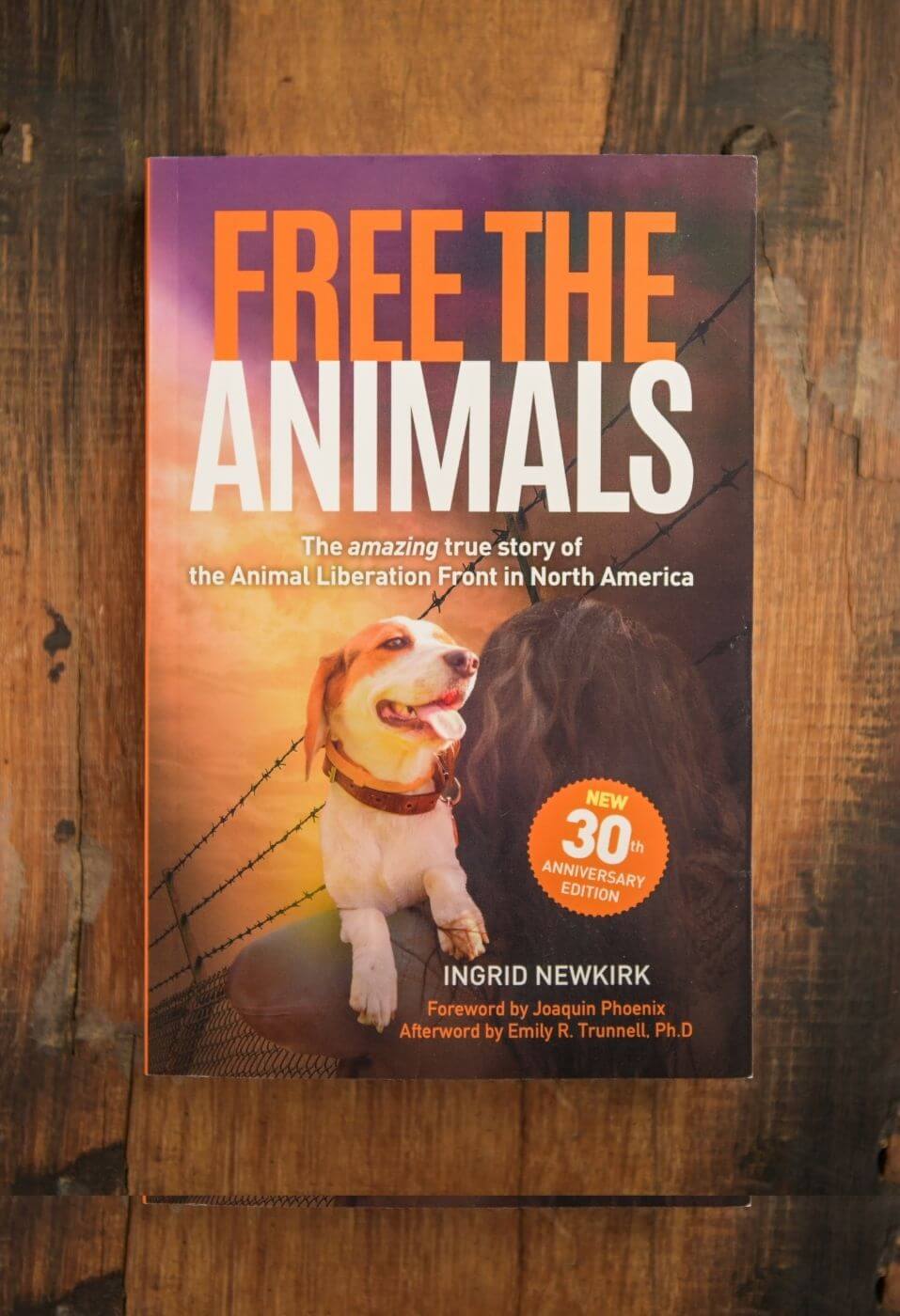

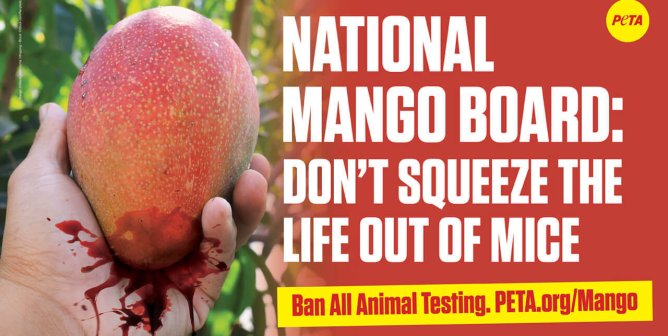

Animals are not ours to experiment on, eat, wear, use for entertainment, or abuse in any other way.

Animals

We are all animals.