The Grim Reality of Animal Experiments at Virginia Commonwealth University

PETA is pulling back the curtain on taxpayer-funded animal experiments at Virginia Commonwealth University.

- Official Animal Welfare Concerns

- Number of Animals Used

- Examples of Animal Experiments

- “Column E” Animals Used

- Media Coverage

- Public Funding

Official Animal Welfare Concerns at VCU

Every year, Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) uses an untold number of animals in experiments, including dogs, nonhuman primates, sheep, rabbits, mice, rats, guinea pigs, and pigs.

VCU’s website states that the university “employs the following ethical mandates, known as ‘The Three Rs’ of animal research.

- Reduction: Required evidence that the number of animals is reduced to the smallest number possible (respecting the value of each life)

- Replacement: Required evidence that a non-animal model is not available and/or that the species identified is justified (replacing animal use where feasible)

- Refinement: Required evidence that all procedures ensure the highest quality of compassionate care and comfort (applying standards developed to ensure quality of life through the minimization of risk and discomfort, adequacy of housing and advanced veterinary medicine)”

Oversight agencies responsible for ensuring compliance with federal animal welfare standards have documented numerous issues at VCU:

- Two mice were found dead, and one was lethargic “due to dehydration.” A valve on their water dispenser had become displaced, and the mice were confined without access to water. The animals’ “caretaker did not recognize the declining health of the mice in the cage during comprehensive observations over the weekend and the following Monday morning, contributing to the situation.”

- Two mice died and four others were found lethargic after several workers failed to notice that they lacked food for four days. The four surviving mice were killed.

October 12, 2022, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2S)

- Three mice died of dehydration after a water sipper tube to their cage became partially clogged by pieces of rubber from a dry, rotted seal. Workers had also placed a plastic “Mouse House” in the front of the cage obstructing their view of the animals and making adequate monitoring impossible.

February 23, 2022, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2R)

- One mouse died and three others in the same cage were lethargic due to lack of food. Four mice in another cage were also deprived of food and found to be lethargic. The worker who took these unweaned pups from their mother had failed to put food in the cages, and workers failed to notice the absence of food during checks over the next three days. Worker key card scans were later analyzed, showing that they hadn’t spent sufficient time per cage evaluating animal health and checking food and water levels.

December 20, 2021, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2Q)

- One mouse died and another was found in a weakened state after they weren’t given food for at least three days. An experimenter hadn’t provided food to the mice, and the weekend workers had failed to notice the animals had no food. The food dispenser had also been placed backward in the cage, so there was no way for the animals to eat.

December 20, 2021, NIH OLAW Report (2P)

- Six dead newborn mice and one live newborn mouse were found in a cage scheduled to be washed. A worker had apparently moved the cage to the pre-washing area without checking whether there were mice inside. The surviving mouse was killed.

September 15, 2021, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2O)

- Twelve mice were subjected to research activities after the approved protocol had expired.

July 20, 2020, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2N)

- A female mouse was found dead in a cage with a male mouse and seven pups. A worker removed her body but didn’t add supplemental food for the other animals or notify veterinary staff. Three days later, six pups were found dead and the seventh pup was killed.

March 10, 2020, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2M)

- Four recently weaned mice were found dead after not being provided with access to water for approximately five days. NIH OLAW responded with a warning that if another animal died from lack of food or water, the facility would be placed on an “enhanced reporting schedule.”

February 7, 2020, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2L)

- Two mice died after workers failed to provide them with access to food or water for between two and eight days.

January 15, 2020, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2K)

- Ninety-eight rats underwent corneal graft transplant surgery with a lower dose of pain-relieving medication than outlined in the approved protocol.

December 16, 2019, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2J)

- Fifty-seven mice underwent surgery and were not administered pain-relieving medication per the approved protocol. Two mice died, and six others were killed.

August 7, 2019, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2H)

- Four mice were found dead after a worker incorrectly placed their food in a way that prevented the mice from accessing it. Two days later, two additional single-housed mice were found dead after a worker incorrectly placed their water dispenser and food in a way that prevented them from accessing it.

August 7, 2019, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2I)

- After being left without water, two mice died and two became lethargic and were killed. A worker “had brought the cage to the laboratory for training but forgot to return it to the vivarium.” The two surviving mice were killed.

June 26, 2019, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2G)

- A worker failed to provide treatment or notify veterinary staff after noting two mice appeared lethargic. The mice died and were cannibalized the following day. Food pellets had obstructed the water bottle holder, preventing the mice from accessing water. In a separate incident, three mice couldn’t access water after a worker placed the water bottle improperly and used the wrong size sipper tube. One mouse died of dehydration, and the other two appeared lethargic and were killed.

May 28, 2019, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2F)

- Three mice died of dehydration because the water level in their water pouch was too low for them to access.

May 19, 2019, Self-Reported NIH OLAW Report (2E)

- Three cages of mice were found with empty water pouches. “Two cages contained nine dead mice. Five mice in the third cage recovered with supportive treatment.” Necropsies determined dehydration as the cause of death.

- No post-operative observations were documented in the records of five rabbits who had undergone a surgical procedure. One rabbit had a wound that had not been observed, documented, or reported to the veterinarian. An experimenter later determined that the rabbit’s surgical incision had split open.

Number of Animals Used at VCU

VCU submits an approximate number of all animals used in experiments to the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International annually in order to maintain accreditation. This number includes commonly used species not covered by the federal Animal Welfare Act (AWA), such as amphibians, reptiles, fish, invertebrates (including crustaceans and insects), birds, rats of the genus Rattus, and mice of the genus Mus, who are “bred for use in research.” According to the AAALAC annual report for 2022, species not covered by the AWA—mice, rats, birds, and cold-blooded species—accounted for 99.4% of the animals used at VCU.

| Type of Animal | Number Used |

| Amphibians | 65 |

| Birds | 509 |

| Chinchillas | 30 |

| Fish | 16,202 |

| Mice | 21,165 |

| Pigs | 22 |

| Rabbits | 221 |

| Rats | 2,718 |

| Total | 40,902 |

“Column E” Animals Used by VCU

Animals who likely experienced pain or distress and who were deprived of appropriate anesthetic, analgesic, or tranquillizing drugs due to possible adverse effects on the data are included under “Column E” in facilities’ annual reports.

- 2022: Column E Explanations

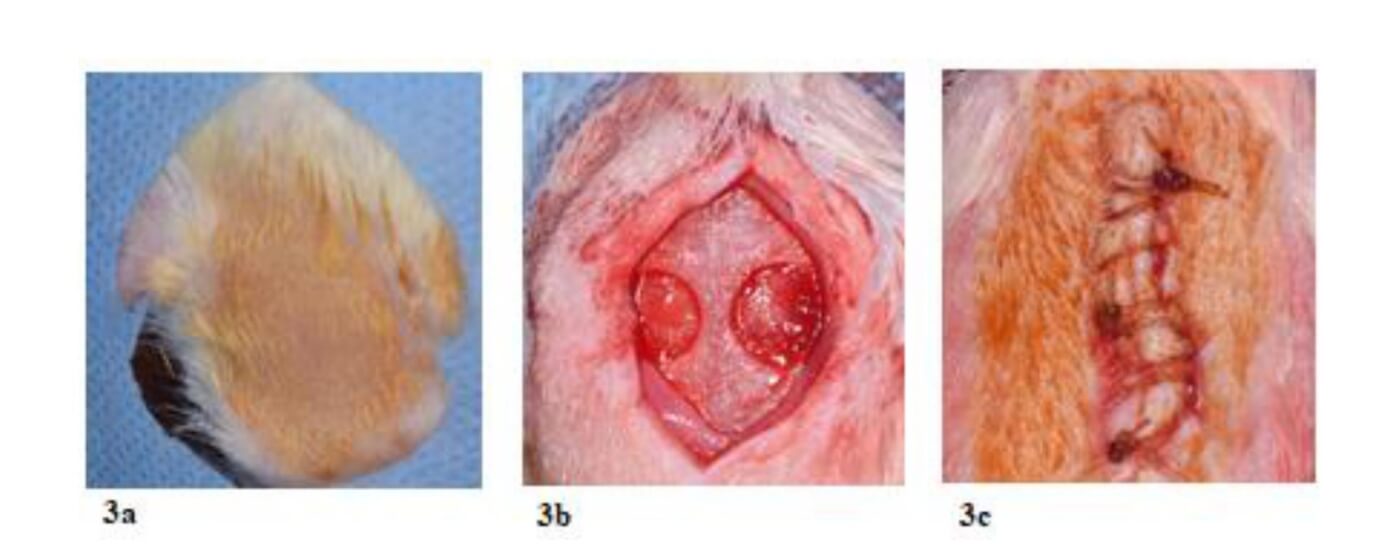

- Forty-seven rabbits were used in experiments in which they underwent tibial nerve surgery and were then denied analgesics for one week, at which point they underwent another surgery (this one terminal). The experimenters acknowledged the “inherently painful nature of nerve injuries” but claimed that analgesia “may alter data and alternative methods of addressing discomfort will be discussed.”

- 2021: Column E Explanations

- Eighty-three rabbits were used in experiments in which they underwent tibial nerve surgery and were then denied analgesics for one week, at which point they underwent another surgery (this one terminal). The experimenters acknowledged the “inherently painful nature of nerve injuries” but claimed that analgesia “may alter data and alternative methods of addressing discomfort will be discussed.”

- 2020: Column E Explanations

- Five rhesus macaques were used in an experiment creating opioid dependence and examining withdrawals. Experimenters claimed that the use of anesthetics, sedatives, and analgesics “would obscure our evaluation of the opioid withdrawal signs” and that “the distress produced by this procedure is the scientific end-point being measured.”

- 2019: Column E Explanations

- Three rhesus macaques were used in an experiment creating opioid dependence and examining withdrawals. Experimenters claimed that the use of anesthetics, sedatives, and analgesics “would obscure our evaluation of the opioid withdrawal signs” and that “the distress produced by this procedure is the scientific end-point being measured.”

- 2014: Column E Explanations

- Three rhesus macaques were used in an experiment examining opiate withdrawal. Experimenters claimed that the use of anesthetics, sedatives, and analgesics “would obscure our evaluation of the opioid withdrawal signs” and that “the distress produced by this procedure is the scientific end-point being measured.”

Examples of Animal Experiments at VCU

The following experiments were recently conducted at VCU, and most were publicly funded:

Lorcaserin maintenance fails to attenuate heroin vs. food choice in rhesus monkeys.

Experimenters surgically implanted tubes into rhesus macaques’ veins and attached the external part of a catheter to a tether connecting the monkeys to a cage. The monkeys could then push a lever to self-administer heroin, or they would receive a pellet of food. Several of the monkeys had previously been used in experiments in which they self-administered cocaine or opioids.

Selective inhibition of soluble TNF using XPro1595 improves hippocampal pathology to promote improved neurological recovery following traumatic brain injury in mice.

Experimenters caused traumatic brain injury to mice through “controlled cortical impact,” in which a rod was rapidly accelerated into the exposed brain. Experimenters then subjected the mice to neurological tests, including a water maze in which they were forced to find an arbitrarily placed platform in a pool of water, purportedly to test their “spatial learning and memory.” In another test, experimenters measured mice’s “hindpaw hypersensitivity” by confining them under a glass beaker and repeatedly poking the pads of their feet with plastic filaments until the mice withdrew, licked or shook their feet, or rapidly moved away from the stimulus. These tests determined that the mice experienced “deficits in learning and memory, depressive-like behavior, and neuropathic pain.” The mice were then killed.

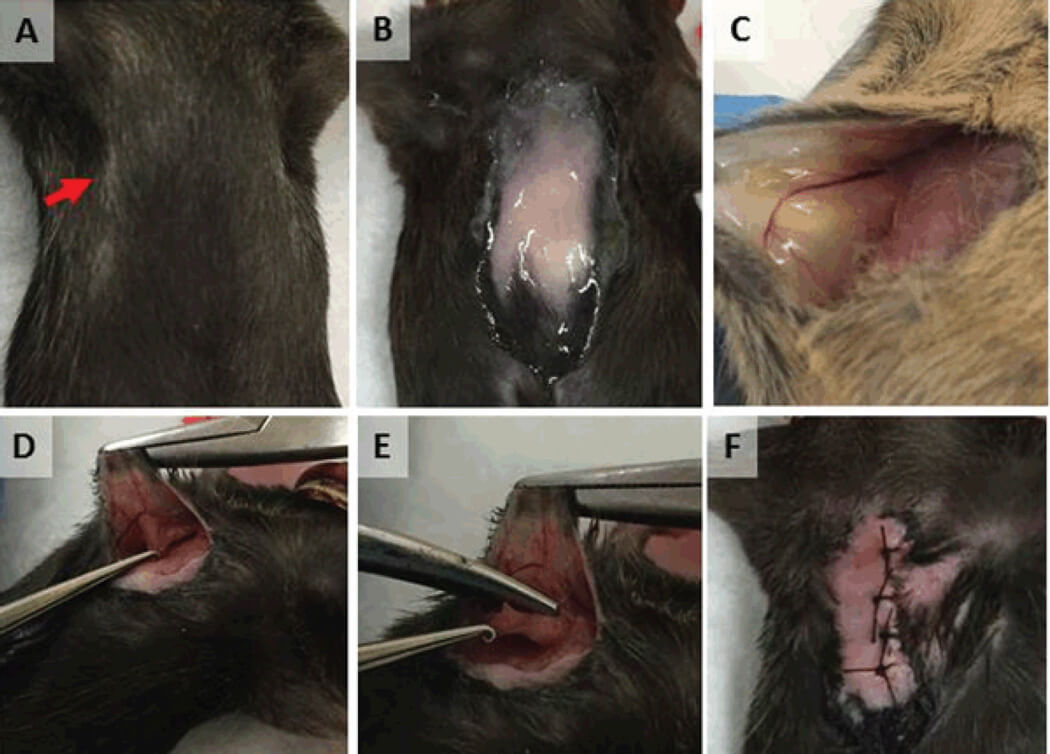

Reambulation following hindlimb unloading attenuates disuse-induced changes in murine fracture healing.

Experimenters repeatedly suspended mice by their tails over a period of three weeks to induce significant bone and muscle loss. The experimenters then surgically fractured the mice’s femurs (thigh bone). Between four and 14 days after the fracture, the mice were killed.

Chronic adolescent stress causes sustained impairment of cognitive flexibility and hippocampal synaptic strength in female rats.

Experimenters subjected adolescent rats to chronic stress through a battery of procedures. The rats were subjected to “social isolation, social defeat, and restraint stress,” in which each rat was placed in a cage with an older rat known to be aggressive, placed in an acrylic restraint just larger than the rat’s body for a full hour, or placed in solitary confinement for a period of 12 days. After inducing chronic stress through these procedures, the experimenters used a maze to assess the rats’ “spatial learning and memory.” The animals were then killed.

What is a multisensory cortex? A laminar, connectional, and functional study of a ferret temporal cortical multisensory area.

Experimenters restrained the heads of ferrets in a metal frame, removed a portion of their skulls to expose their brains, and “a recording well/head support mount was implanted using screws and dental cement.” The experimenters then recorded the ferret’s “auditory responsiveness” to a dog-training clicker, “visual sensitivity” to a flashlight or moving black card, and their reaction to physical stimuli by “lightly tapping the body surface with a fine camel’s hair brush.”

Media Coverage Concerning Animal Testing at VCU

- May 28, 2015: “Universities, Feds Fight to Keep Lab Failings Secret,” USA Today

- February 3, 2018: “ Barton Hinkle: What Is VCU Doing to the Animals?” Richmond Times-Dispatch

- April 26, 2018: “Monkeys being used for opioid research at VCU; graduate calls for transparency,” ABC8 News

- May1, 2018: “We gotta get people out of the hospital: VCU researcher defends taxpayer-funded animal testing,” ABC8 News

- October 16, 2018: “PETA pushes for VCU to end opioid testing on lab monkeys,” The Commonwealth Times

- February 21, 2023: “Virginia bill would require animal testing facilities to submit info to the state,” The Virginian-Pilot

- June 12, 2023: “Amid ODU, EVMS and other university citations, Virginia senators call for more animal testing accountability,” The Virginian-Pilot

- February 8, 2024: “Bipartisan bill on animal testing transparency is downgraded to study after industry pushback,” The Virginian-Pilot

Public Funding for Experiments on Animals at VCU

In 2021, the Commonwealth of Virginia and its localities gave public universities more than $130 million for animal and non-animal research. Currently, no information is available indicating how much money is spent on animal experimentation alone in Virginia. The table below shows the total annual research funds received by VCU for the past eight years, including public funding.

In 2023, VCU spent $7,723 of its funding on AAALAC “accreditation” fees.

| Year | State/Local Govt. | Federal Govt. | All Sources |

| 2014 | $6,692,000 | $138,559,000 | $201,858,000 |

| 2015 | $6,698,000 | $142,447,000 | $218,925,000 |

| 2016 | $5,236,000 | $143,701,000 | $225,999,000 |

| 2017 | $4,991,000 | $147,585,000 | $235,464,000 |

| 2018 | $25,822,000 | $140,363,000 | $246,190,000 |

| 2019 | $27,123,000 | $142,293,000 | $255,648,000 |

| 2020 | $28,217,000 | $152,751,000 | $283,874,000 |

| 2021 | $31,893,000 | $160,995,000 | $364,096,000 |

| 2022 | $34,539,000 | $166,726,000 | $405,898,000 |

Source: Higher Education Research and Development Survey, Table 83 for FY 2014, Table 82 for FY 2015, and Table 5 for FY 2016–2022