Elephant Calf Taken From His Family in Australia to Be Bred at Zoo Miami

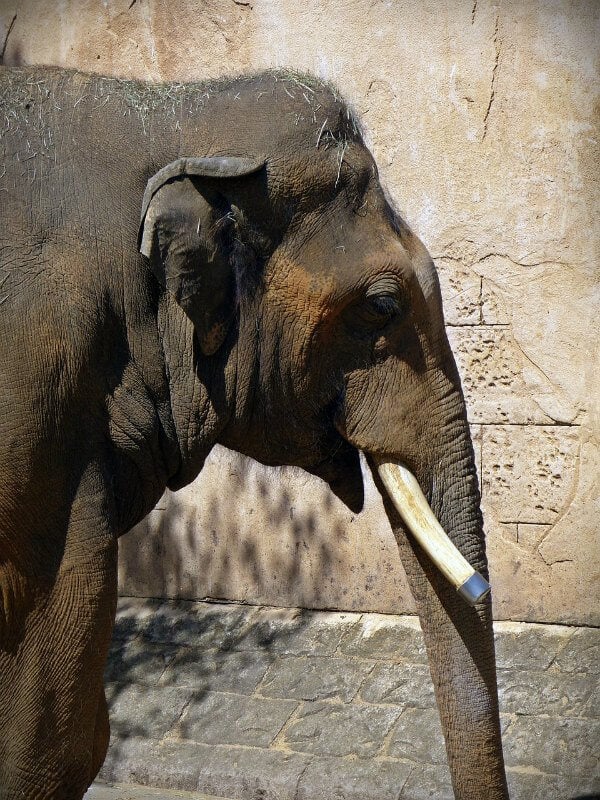

A 7-year-old elephant calf named Ongard is without his mother, siblings, or any other familiar elephants for the first time. He was taken from his family at Australia’s Melbourne Zoo, where he has lived all his life, and sent to Zoo Miami to be used to breed more elephants for captivity.

Despite what zoos would have people believe, breeding captive elephants does nothing to contribute to the survival of the species in the wild.

And Ongard won’t be the last elephant that this happens to: He’s “owned” by the Zoological Society of San Diego, which has signed a contract with the Australian organization Zoos Victoria to transfer elephants deemed “non-essential” in order to diversify their countries’ respective captive gene pools.

Much like SeaWorld does, zoos routinely take captive animals from their families and transfer them to other facilities with unfamiliar animals in order to use them for breeding. Babies equal ticket sales for animal attractions.

Zoos continue to breed elephants, despite knowing the immense toll that captivity takes on their physical and mental health. Among numerous other problems, captive elephants have high infant mortality rates and low life expectancy, and they often suffer from degenerative joint disease—which, while unheard of in nature, is a leading reason why captive ones are euthanized.

Elephants rarely breed naturally in captivity, so Ongard will be subjected to highly invasive “collection” procedures, and his sperm will be sent to other zoos so that they can inseminate female elephants. Semen is collected from males through either rectal massage or electro-ejaculation, in which a probe is inserted through the rectum and into the lower intestine and used to send a jolt of electricity into the elephant’s body. During both processes, the animal is either restrained, sedated, or anesthetized.

The insemination procedure may take hours to perform on females. Feces are manually removed from the rectum, which is then flushed out with water. A catheter is inserted into the elephant’s 8-foot-long reproductive tract to penetrate deep into the uterus. Staff monitor the procedure using an endoscopic camera inside the elephant’s reproductive tract and transrectal ultrasonography. The procedure is typically repeated many times each cycle—often for years before an elephant ever conceives. The first-year mortality rate for Asian elephants is over 30 percent.

PETA pushed for Ongard to be left with his family. And we continue to call on all zoos to stop moving elephants around like chess pieces.